What is a food system?

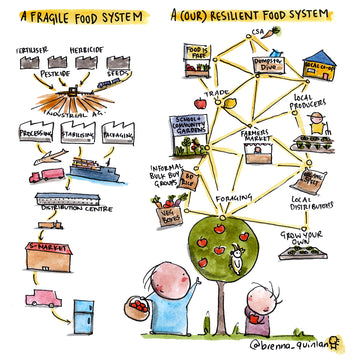

The term “food system” often feels theoretical or abstract, but in essence is the way we, as a community and as individuals, grow, source, and consume food.

It could be as simple as walking to the back yard to harvest your own lettuces, all the way through to consuming imported produce like Californian Oranges.

It encompasses production, transport and consumption. It identifies and often tries to create efficiencies with all the resources that go into each step of the way.

Some food systems are short (aka the garden), some are much longer and more heavily burdensome of resources.

The beginnings of Good Harvest

Good Harvest was founded out of frustration about our local food system.

After travelling globally, Mick saw how connected many communities were to their local growers, and how food was a celebrated part of culture and family. Upon returning to Australia he realised how different it was back home.

The micro communities Mick experienced in South America and abroad, functioned on a simple premise of growing food and consuming it locally. Paddock to plate in a very real sense.

Seasonality was evident and celebrated, and local farmers and producers were acknowledged for their ability to feed their community. Sounds lovely doesn’t it?

Australia's centralised food systems

Contrast the ideal low resource food system to what we have here in Australia, it’s vastly different. It's not just happening in Australia too.

We’ve experienced generations of changes in our food system, including advances in logistics and food manufacturing, but more significantly, the introduction of a centralised food model for supermarkets and greengrocers (think large food hubs like Rocklea Markets in Brisbane).

Farmers and producers sell their produce to agents at the markets, often at a contracted supply amount and price, and then these agents on sell this to retailers (putting their own margin on top).

A centralised food system certainly has some benefits such as:

- Consistent supply – if you want a certain item, you’re likely to be able to get it that same day.

- Extensive range of produce including items that are typically out of season.

- In some cases, it’s easier for growers to work with one wholesaler rather than several small buyers.

From a consumer perspective these benefits reinforce the positive effects of a centralised food system.

The negative impacts of a centralised system on our society

So, what’s the big deal anyway? We’re surrounded by more food than ever before – isn’t that a good thing?

The challenges of a centralised food system are generally hidden and long term in nature – often only coming to light during times of crisis or natural disasters, or not visible at all when farmers go out of business or sell their lands due to economic pressures.

Some of the major impacts of a centralised food system certainly make us shake our heads in disbelief. Its purpose is to remove connection between consumer and producer, making it "easier" for retailers to get produce quickly.

A centralised food system is the opposite of what we are trying to achieve here at Good Harvest. Heres why:

Disconnection between the grower/farmer and consumer

Centralised food systems mean that growers typically drop off a bulk delivery of produce and it is sent out accordingly to various supermarkets. The farmers' connection to their product ends with a warehouse.

Produce is treated as a commodity, rather than celebrated for its contribution to the health of the community. Imagine growing an amazing zucchini or apple and how deflated you’d feel if it was shipped and packed around the country – never knowing if people were actually loving or even eating your produce.

As a consumer, purchasing from a supermarket or even an organic store that operates with a centralised distribution hub, means you’re so far removed from the hands that grow your food.

Scary!!! Being so acutely aware of what we’re consuming, it should raise alarms when we don’t know who grew our food or how they grew it.

Longer food transport times means lower food nutrition, higher costs & more hands

Picture this, an organic farm operates less than 10km drive from a major organic retailer - sounds idyllic! However, with a centralised food system, that organic farm is not allowed to supply direct to the retailer but has to drive their produce 150km to their centralised food hub in Brisbane, only to have it shipped back the next day (or a few days later), to their nearby store……

Um what???

So who bears the cost of this absurdity? Well - everyone:

- the consumer who has to deal with not only higher priced produce (someone has to bear the cost of delivery) and produce that is older than it needs to be

- and the farmer, who still gets the same amount for a head of lettuce if he sells it locally or has to drive it to Brisbane (increased transport and time costs).

Now imagine this on a larger scale - eg supermarkets, and how long produce is being stored and transported before it reaches you!

Centralised food systems also mean that produce changes hands many times before it reaches the consumer. This is especially true if it goes between centralised food hubs in major cities. Imagine how many people have handled that produce, and how many companies have charged a little bit extra on that single item.

Seasonal fluctuations, quality issues and supply are considered an inconvenience rather than a benefit

Anyone else feel like a mango in July? Of course we do! But the fact is, produce is better when it’s in season. Our bodies are designed to crave the right foods at the right time of year. Think warming foods and soups in winter, and fruits and lighter meals in summer.

A centralised food system works against seasonality by bringing in produce from across the globe (Californian oranges - really?). Extending seasonality further through the use of chemicals also means that people have lost touch with the flow of their local growing season.

Commonly we see farmers penalised for not being able to fulfil their growing contracts due to rain or harvest issues. Farming is difficult enough let alone having the added pressure of not being able to supply a contract. Guess what? Nature is a wild unpredictable world, sometimes you can do everything the same and things just don't grow or harvest at the predicted rate. Everybody needs to be ok with this.

Imperfectly real

Centralised food systems also hate imperfect produce. Why? It's harder to sell. Few stones in your avocado, thats ok. Maybe a spot on your apple - its actually really tasty.

Supermarkets have created this idea that we can only eat perfect on time produce. But that means that there is a lot of food going to waste in our quest for perfect shiny apples. Sometimes we need to remember how awesome it is to have all this food anyway, let alone a wonky carrot or funky looking zucchini. PS. Ask how many chemicals it takes to make your apple shiny or your veggies look exactly the same!!

Vulnerable to crisis and supply chain disruptions

You only have to look back 16 months ago to the flooding of 2022 to see the impacts that had on food supply in the supermarkets. The shelves were very empty. The centralised food hub was flooded which means produce cannot get from producer to consumer. In this example it's a lose / lose situation.

The farmer who may not be affected by flooding, cannot get their produce to market, loses crops, and the consumer cannot access the produce.

COVID was a similar experience. Disruptions are frequent and a centralised food system is a vulnerable model. Simply put – it doesn’t take much to rock the boat and affect supply in a centralised food system.

Conversely, in a decentralised model, impacts are far less reaching. Micro communities operate independently yet are also interconnected – the links are founded on community, not commodity. In short, everybody works together!!!!

The way forward

We believe the way forward is found by going backwards. Yes times were simpler, but in the past, it was easier to meet your needs right in your own community

Here's our top six ways to reverse the impacts of centralised food systems:

- Know your farmer, know your food! Connect with your local growers so you can learn all about what how and when they are producing.

- Be ok with produce that isn't perfect - grown by nature

- Join a community garden or harvest swap - connect with your community and share food

- Grow your own! Even just a few things - trust me it feels awesome!

- Eat local, in season produce - it'll be fresher, more nutritious and tastier

- Buy direct wherever possible or ask your retailer where the produce is coming from? In fact, ask your retailer if they use a centralised food system and help them find ways around it.

📷 Image Credit @brenna_quinlan